On a typical VFR summer day in southern Canada or the northern US — the kind that the weather(wo)men call “a mixture of sun and cloud” with a decent amount of humidity — swirling columns of heated air, called thermals, start rising in the morning, and get higher and higher into the late afternoon as the sun warms the ground.

Clouds are the dividing line

At the top of those thermal columns, like scoops of ice cream on top of invisible cones, scattered cumulus clouds form. At first, those clouds might be only 1,000 feet thick and maybe 2,000 ft above the ground, but as the columns rise, the clouds get both higher and thicker, and some of them may develop into storm clouds during the afternoon (giving your typical cottage thunderstorm or 20-minute shower).

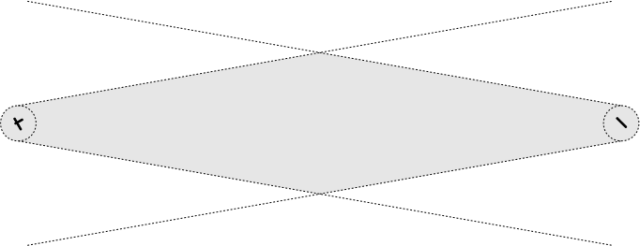

Underneath those clouds the horizontal winds are weaker, but the vertical motion of the thermals can cause a lot of turbulence — while the air may be smooth at breakfast, by early afternoon it can be rough enough to have passengers grabbing for the vomit bags, while the pilot feels like he or she is in a wrestling match with the yoke and rudder pedals.

Above the clouds, the air is normally smooth, but the winds are much stronger.

So where do you fly?

Flying eastbound

Eastbound, the best place to be is above the clouds if you (and your plane) can manage it. Prevailing summer upper winds in this part of the world are from the west or southwest, so on a good summer’s early afternoon you can get a 25-30 knot tailwind and smooth air at 9,500 ft eastbound. What’s not to love?

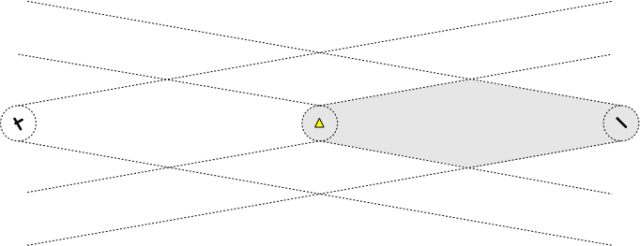

The problem is that the tops of those cumulus clouds keep getting higher and higher until almost supper time. In Canada, you need oxygen to fly above 10,000 ft for more than 30 minutes, and the tops of summer cumulus clouds could hit that height anywhere between 11:00 am and 2:00 pm, even ignoring isolated storm clouds. As the day goes on, without oxygen and a powerful plane, you hit a point that you can’t outclimb the clouds any more, and you’re forced to descend either into them (IFR) or under them (VFR), giving up some of the tailwind, and throwing you and your passengers back into the turbulence.

The good news is that, with the extra speed from the tailwind, you might be able to finish your trip before that happens. It’s possible to fly a Piper Warrior from Ottawa to Charlottetown in well under four hours with a good tailwind, so you can leave early in the morning, fly non-stop, and land for lunch before the clouds (and turbulence) outclimb you. Your passengers will have to put up with a bumpy descent and landing, but the rest of the flight will be smooth.

Flying westbound

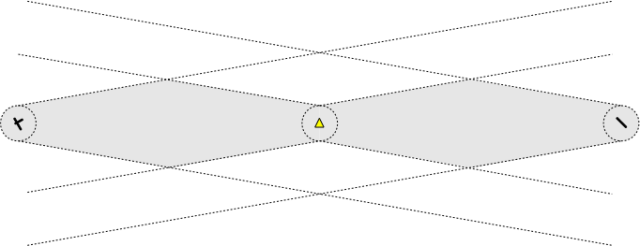

Flying westbound, into the wind, you’re faced with a lose-lose proposition:

- Fly below the clouds to get weaker headwinds, but subject your passengers to stomach-emptying turbulence as the day goes on.

- Fly above the clouds to get smooth air, and watch your airspeed drop to (or below) automobile speeds.

First thing in the morning, you have a good chance to find both smooth air and weak headwinds at low altitudes (e.g. 2,500 ft), but that won’t last until lunch. As the cumulus clouds start to form, you’ll have to pick sides, diving down into the turbulence or climbing up into the headwinds. And to throw extra salt into your wounds, the headwinds slow you down and make it more likely that you’ll have to make a fuel stop, slowing you down even more, and pushing your flight later and later into the afternoon and the worst of the turbulence and/or headwinds. If you do decide to go above, even that won’t last: in a low-end plane without oxygen, you’ll eventually have to go down below and start banging your passengers’ (and your) heads against the ceiling of your plane.

Flying north- or southbound

In Canada, it’s safe to say that most cross-country flying is on the east-west axis, since Canadian cities are spread out in a thin line along the US border. In the US, on the other hand, you’re just as likely to be flying on the north-south axis (or something in-between). In that case, if the upper winds are from the southwest (typical in summer, at least east of the Rockies), then flying southbound will be a lot like flying westbound, but with less severe headwinds, while flying northbound will be like flying eastbound, but with less beneficial tailwinds.

Strategies

I fly some passengers who suffer from motion sickness, so I spend a lot of time planning around this stuff. In general, flying eastbound, I’ll go up above and accept a longer flight to get smooth air, since my passengers would rather be comfortable for 5-6 hours than violently ill for 3-5. Still, I can’t protect them from the turbulence when I have to land (fuel stop or destination).

Of course, I can’t stay above all day when the sun’s out — today, coming back from Charlottetown, I started at 2,500 ft in air so smooth you could do calligraphy in the back seat, but by late morning ended up at 10,500 ft over Quebec’s Eastern Townships trying to stay above the rising cumulus layer. Once my 30 minutes above 10,000 ft were up, I had to descend and subject my passengers to 40 minutes of turbulence below the clouds at the end of the flight.

If your schedule can handle it, there are some workarounds to minimize the damage:

- Start as early in the morning as possible, if there’s no fog or low stratus. Some pilots I’ve met like to be preflighting as the sun rises. If your family is willing to wake up at 5:00 or 5:30 am, go for it, and the flight will be more fun (plus you’ll have more of the day at your destination).

- If your route follows a shoreline or a wide river, fly over water instead of land (staying within gliding distance). Water tends to be cooler in the summer, and doesn’t throw up thermals as much. Often, the best break through a line of thunderstorms will be over water, but don’t let yourself get pushed offshore.

- Fly in the evening, especially if you have a well-lit destination for landing after dark. Summer evenings are long-ish, and the air tends to start calming down again around 7:00 pm, give or take, as the ground cools, the thermals die out, and the afternoon cumulus clouds flatten out and disperse.

- Split up the trip. Instead of two three-hour legs with a fuel stop on your westbound flight, fly halfway, land before lunch, and spend the day. The next morning (or that evening), fly the second leg in smooth air again. For example, I could have flown from Charlottetown to Quebec City, spent an afternoon and evening there, and then flown on to Ottawa the next morning.

- Stay on top as long as possible, and descend quickly at your destination. For passengers who suffer from motion sickness, popping ears are far preferable to a long time down low in turbulence.

- Take up soaring. Glider pilots love afternoon thermals, because the rising air lets them stay up almost indefinitely — that’s why you’ll often see gliders happy circling under a cumulus cloud, while pilots of powered planes are impatient to be back on the ground.

In the end, though, turbulence and headwinds are facts of summer flying, and not every day is a typical day — you could drag everyone out of bed at 4:30 or 5:00 am and still be in bumps the whole flight, and you could even end up with headwinds in both directions. Don’t pressure yourself to make the flight perfect and control things outside your control: just do your best with whatever you have to work with.